Mondo CEO Tom Blomfield doesn't look like a typical banker, and he doesn't want his mobile app to behave like a typical bank.

Tom Blomfield, the 29-year-old CEO of Mondo, says his grandmother wouldn't bank with his app, but he's betting a big segment of the U.K. population would.

On a sweltering afternoon in July, Tom Blomfield emerges from Bank of England offices in the heart of the City of London and promptly sheds his suit jacket. Blomfield, the 29-year-old, bearded CEO of Mondo, a startup smartphone bank that’s applying to operate in the U.K., isn’t the suit-wearing type. He’s eager to get back to his Clerkenwell workspace for a beer to celebrate Mondo’s surmounting a big hurdle in its quest for a banking license.

Blomfield and his team have just spent two hours getting grilled by eight regulators from the Bank of England and the Financial Conduct Authority, Bloomberg Markets magazine reports in its October issue. The officials quizzed them on how Mondo will attract customers and remain financially viable. After poring over Mondo’s 250-page submission, which included details of its capital and liquidity plans, the group pressed Blomfield on why he wanted to run a bank. “They said he didn’t look like a typical banker,” recalls Mondo Chairman Denise Kingsmill, who, as a member of the House of Lords and a former deputy chairman of the U.K.’s Competition Commission, added a touch of gravitas to the presentation.

Blomfield had a ready retort: “I said I want to run a new type of bank.”

When he’s not trying to charm regulators, Blomfield shows the kind of passion—and irritation—it takes to build a bank from scratch. His catalog of complaints about big lenders is familiar to most consumers: hours of paperwork to open an account or apply for a loan, exorbitant fees for using your credit card abroad, onerous overdraft charges, and clunky mobile apps. “I wake up and say: ‘My bank is so bad. These guys are dinosaurs!’” Blomfield says. “It impacts me, my family, all my friends. We all have to use banking, and it’s broken.”

Blomfield wants to make Mondo the Google or Facebook of banking with accounts that are as easy to use as e-mail. “We are targeting a demographic that values being able to do everything over a mobile phone in five seconds,” he says.

If Blomfield and Kingsmill get their way, Mondo won’t be just another snazzy app using the license of an existing bank. That’s been done in the U.S. by Simple.com, which piggybacks onto Bancorp Bank, and in Germany by Number26, which is bolted to Wirecard Bank. Unlike most other startups, Mondo has built proprietary software. If Mondo gets a license from the BOE’s Prudential Regulation Authority, it could—as early as next year—begin taking deposits and lending money.

Denise Kingsmill, a member of the House of Lords, serves as Mondo's chairman

Should Mondo pass muster, it might thank Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne. He’s overseen the regulatory revamp that’s made it easier for startup banks to get off the ground. In a speech last year at Canary Wharf tech accelerator Level39, Osborne said he wanted to make London the “fintech capital of the world.” In March, he said the Bank of England should grant at least 15 new licenses in the next five years.

“Osborne is a real tech geek,” says Rohan Silva, a former technology adviser at 10 Downing Street, pointing out that the chancellor learned to code as a teenager. “Investors and entrepreneurs haven’t started new banks in this country because they knew the regulators wouldn’t let them,” he says. “We thought if we took away regulatory barriers, fintech would explode.”

When it comes to British banking, such innovation looks long overdue. The big four banks—Barclays, HSBC Holdings, Royal Bank of Scotland Group, and Lloyds Banking Group—control 77 percent of the U.K.’s 65 million personal checking accounts. Customers aren’t overwhelmingly happy with the available choices. Only 60 percent say they’re satisfied with their bank, a 2014 survey from consulting firm Accenture found.

It used to be exceedingly difficult to start a bank in the U.K. The process took years and required millions of pounds in upfront capital, without any indication whether regulators would give their seal of approval. When a bricks-and-mortar lender called Metro Bank opened its doors in 2010, it was the first new retail bank U.K. regulators had authorized in 100 years—and it took them almost two years to OK it. Today, Metro has more than 500,000 customers, and deposits surged 188 percent to £2.9 billion ($4.5 billion) last year. While Metro’s branches are open seven days a week and feature amenities such as water bowls for dogs, the bank began offering a mobile app only last year.

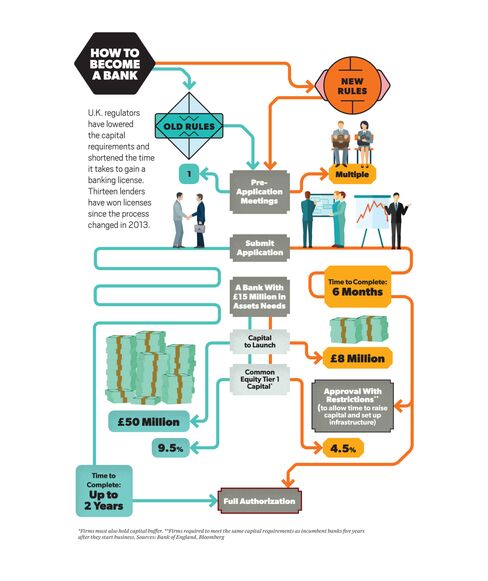

The application process is now simpler—for both physical banks like Metro and digital ones like Mondo. Under BOE and FCA rules, a new entrant can hold as little as £1 million in capital initially. An applicant needs common equity Tier 1 capital of 4.5 percent of risk-weighted assets, significantly less than the 9.5 percent required under the old rules that still apply to existing banks. The Bank of England says it will use its discretion to give startups more time than before to build the additional capital required under Basel III.

“Regulators here are much more progressive and open than in the U.S.,” says Eileen Burbidge, an American who’s a partner at Passion Capital, the London venture firm that in April gave Mondo $2 million in seed money. “If you’re doing leading-edge fintech, London is the place to be.”

Indeed, investment in fintech companies is growing faster in the U.K. than it is anywhere else in the world. Last year, London’s fintech startups attracted £343 million, triple the amount invested in the previous year, according to London & Partners, a firm set up by London Mayor Boris Johnson to promote the city. U.K. fintech companies raised £306 million in the first half of 2015 alone. With venture capital red-hot for fintech, Mondo’s goal to attract a further $15 million to begin operating as a bank looks modest. The sum would cover additional hiring and marketing as well as initial capital to back any lending losses.

Eileen Burbidge is a partner at Passion Capital, which gave Mondo $2 million in seed money

More banks are getting the green light—and getting it faster. Thirteen have won licenses since the regulatory changes in 2013. In June, Atom Bank became the U.K.’s first digital-only lender to secure approval, just six months after it formally applied. It expects to begin opening accounts next year, focusing on its mobile app to target small and medium-sized businesses and consumers.

Atom likely will beat Mondo to the market. It has attracted £25 million in financing from such big names as Jim O’Neill, the former Goldman Sachs economist who’s now the U.K. Treasury’s commercial secretary, and venture capitalist Jon Moulton. “It’s in everyone’s interest to digitize as much of the customer experience as you can because it costs less,” says Mark Mullen, Atom’s CEO, who ran First Direct, the telephone bank set up by HSBC in 1989. Atom hasn’t revealed details of its mobile app. Mullen says only that he hopes to use biometric security and locational data to enrich the offering.

In contrast, Mondo is an open book. It’s in the process of rolling out a prototype app and prepaid MasterCard to 500 people initially to get feedback on which parts are popular and which aren’t. “We don’t want to be building a bank behind closed doors,” Blomfield says. “The real value is not in the ideas but in the execution.”

Blomfield’s time at Silicon Valley incubator Y Combinator in 2011 shapes his approach, so much so that he sometimes dons a T-shirt with the Y Combinator motto: “Make Something People Want.” Blomfield earned a law degree at the University of Oxford. A few years later, he teamed up with two fellow Oxford grads to build GoCardless, a simplified system for companies to accept recurring payments. Today, it’s used by the Guardian to collect subscriptions and the U.K. government for road taxes. Blomfield still has a stake in GoCardless, which processes $1 billion of transactions a year.

Once GoCardless was up and running, Blomfield set his sights on banking for consumers. He joined with experienced bankers to get Mondo off the ground. The chief risk officer is Paul Rippon, the former head of operations at Allied Irish Bank; the chief financial officer is Gary Dolman, the former CFO of Japan’s Mizuho Internationa

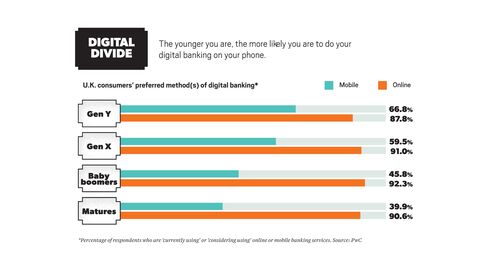

Gen Y is embracing phone-based banking in greater percentages than other generations.

While technology has changed every aspect of our lives, Blomfield says consumer banking has remained frozen in time. Banks continue to offer customers a static list of deposits and withdrawals rather than providing timely updates or useful tools to analyze spending or saving. In a world of instant messaging, many lenders don’t communicate in real time. Blomfield’s current bank (which he declines to name) took two weeks to alert him he’d overdrawn his account by £800 and then charged him £20. “The banks have their hands in your pockets constantly, taking money out,” he says.

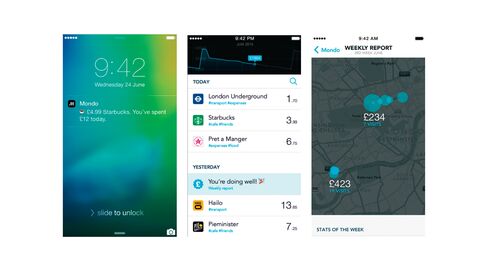

The Mondo app is designed to tell you if you mess up. It lets you set up real-time notifications that say how much you’ve spent daily or whether you’re going into overdraft. If you need £500 to tide you over to payday, Mondo will tell you how much it will cost for a short-term loan instead of charging you after the fact.

Pulling out his phone, Jason Bates, Mondo’s 43-year-old co-founder and chief customer officer, shows his Mondo prototype app. He’d just had a burger with his wife at Five Guys in Soho, which turned up immediately on his account with a map of where he’d used his Mondo card. With a swipe, he demonstrates how you can turn off the card if you lose your wallet and immediately turn it back on if you find it. You can even block your card at pubs to encourage a dry spell.

By tracking your regular bills, Mondo can alert you if something is out of the ordinary, like a utility charge that’s higher than normal. This smarter use of data can help detect fraud, Bates says. “We see your phone is in Manchester but your card was being used in London,” he says. “We can block your card and send you a text saying: ‘Something is fishy. Can you confirm?’”

Mondo's app lets you track expenses as you spend and provides weekly reports

Blomfield and Bates say Mondo could charge much lower fees and still become profitable because its cost base is a fraction of what major banks shoulder. Old-style lenders are saddled with the expenses of maintaining branches and updating antiquated IT systems.

Back-end computer systems that process transactions can date to the 1970s and have had meltdowns, says David Parker, head of banking at Accenture in London. Last year, British regulators fined RBS £56 million for a computer failure in 2012 that left 6.5 million customers without access to their accounts for weeks after a contractor updated software. The problems “revealed unacceptable weaknesses in our systems,” Philip Hampton, RBS’s chairman, said.

“It’s difficult to build an app that’s fantastic when you have an ugly core banking system,” Parker says. “The banks have to change quickly or they run the risk their customers will desert them.”

Not everyone is convinced tech-savvy banks will lure enough customers from the big four to become major players. New fintech banks may have a hard time attracting more than just “hardcore money geeks,” says James Moed, a consultant to fintech startups and a former director of IDEO, where he was a London-based financial services designer. “Most people find managing their money boring and regard banking as a utility,” Moed says. “I’m not sure great apps will motivate people enough to switch.”

Even so, mobile bank users globally are forecast to more than double by 2019, according to a 2015 KPMG report. Generation Y, the so-called millennials, born from the 1980s to the early 2000s, may be the most fertile hunting ground. Almost 67 percent prefer mobile apps for banking, compared with 46 percent of baby boomers, aged 51 to 69, according to PricewaterhouseCoopers. A study by Viacom’s Scratch research unit called “Sorry Banks, Millennials Hate You” found 71 percent of 18- to 34-year-olds would rather go to the dentist than listen to what their bank says.

Blomfield acknowledges that Mondo isn’t for everyone. “My grandmother would not use this bank,” he says. “But a big segment of the population would.”

He likens the banking behemoths to Blockbuster Video, while digital startups such as Mondo are like Netflix. With the right technology and open-minded regulation, Blomfield says, even as staid and entrenched an industry as retail banking can be disrupted. “We think,” says the guy who doesn’t look like a typical banker, “there will be a generational shift in how banking works.”

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario